COVID-19 Portfolio: Scholarship

Articles

"Caring for Capitalism," by Joanna Radin

IT WAS THE mid-1970s, and medicine’s so-called golden age was beginning to lose its luster. The pharmaceutical industry was booming, a sure sign to some that the medical profession had sold its soul — if it ever had one to begin with — to big business. Indeed, that was what Ivan Illich, a Catholic priest and philosopher, charged in a damning, if arcane, attack on what he called the “iatrogenic” culture of medicine: its healers’ tendency to bring forth harm.

Illich did not believe physicians were intentionally trying to hurt their patients. Rather, he blamed the system in which they practiced, one that was oriented toward a dispassionate embrace of science at the expense of humility and humanity. As a spiritual thinker, Illich held a deeper concern that doctors had become cogs in an institutional machine that robbed them of the ability to adequately address human suffering. In 1975, Illich’s takedown of the profession, Medical Nemesis, became a nonfiction best seller.

"Never Ending Stories: Narrating Frozen Evidence of Infectious Epidemics Past," by Joanna Radin

"Frozen by the Hot Zone," by Joanna Radin

Ebola’s ability to travel has been well publicized, but there is another story: one of immobility. In West Africa, research materials that contribute to improving knowledge about the disease such as blood samples and patient records have been trapped or entangled in the “hot zone.” In some circumstances, the virulence of such materials appears to pose a risk to biosecurity that may be greater than their ability to help mitigate that risk. In times of uncertainty, fear may trump established policies about how to manage the flow of people, information, and research materials. For instance, while the World Health Organization (WHO) has been opposed to travel restrictions to ensure continued circulation of health workers, the home institutions that employ such workers may choose to impose such restrictions. In such cases, prevention is seen as a preferable alternative to quarantine should health workers return with infection. Yet, physicians and health workers who have been able to travel between makeshift treatment camps in Africa and the resource-rich laboratories and medical centers in the Global North have been frustrated to realize that perceptions of the intensity of the hot zone functions to freeze the otherwise relatively fluid channels of global biomedical infrastructure.

"Epidemiological Concepts and Historical Examples," by William Summers and S.-H. Lim

"The Nature of Fear and the Fear of Nature from Hobbes to the Hydrogen Bomb," by Deborah Coen

"Michael Crichton, Science Studies, and the Technothriller," by Joanna Radin

The decades following World War II saw an unprecedented increase in the scale and scope of science. These developments generated new dreams as well as new nightmares about the potential for science to reshape the order of things. These changes also gave birth to science studies, a discipline that emerged to understand how political power and social life was reconfigured by “big science” and vice versa. One of the most prolific and influential interpreters of these changes is a writer whose oeuvre is often dismissed as too big, too bestselling, too popular, to warrant sustained attention by either science or science studies: Michael Crichton. Yet he is heir to a literary tradition that includes H.G. Wells, Edgar Allen Poe, and Arthur Conan Doyle, all of whom profoundly shaped ideas about science as well as its practice by inhabiting spaces of ambiguity between the possible and the actual.

"Why Did They Die?" Ricardo Ventura Santos, Carlos E.A. Coimbra Jr., and Joanna Radin

"The Experimental Multispecies Household" by Deborah Coen

Books

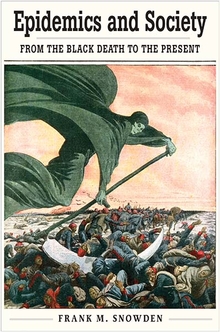

EPIDEMICS AND SOCIETY: FROM THE BLACK DEATH TO THE PRESENT by Frank Snowden

The World Economic Forum #1 book to read for context on the coronavirus outbreak

This sweeping exploration of the impact of epidemic diseases looks at how mass infectious outbreaks have shaped society, from the Black Death to today. In a clear and accessible style, Frank M. Snowden reveals the ways that diseases have not only influenced medical science and public health, but also transformed the arts, religion, intellectual history, and warfare.

A multidisciplinary and comparative investigation of the medical and social history of the major epidemics, this volume touches on themes such as the evolution of medical therapy, plague literature, poverty, the environment, and mass hysteria. In addition to providing historical perspective on diseases such as smallpox, cholera, and tuberculosis, Snowden examines the fallout from recent epidemics such as HIV/AIDS, SARS, and Ebola and the question of the world’s preparedness for the next generation of diseases.

LIFE ON ICE: A HISTORY OF NEW USES FOR COLD BLOOD by Joanna Radin

After the atomic bombing at the end of World War II, anxieties about survival in the nuclear age led scientists to begin stockpiling and freezing hundreds of thousands of blood samples from indigenous communities around the world. These samples were believed to embody potentially invaluable biological information about genetic ancestry, evolution, microbes, and much more. Today, they persist in freezers as part of a global tissue-based infrastructure. In Life on Ice, Joanna Radin examines how and why these frozen blood samples shaped the practice known as biobanking.

The Cold War projects Radin tracks were meant to form an enduring total archive of indigenous blood before it was altered by the polluting forces of modernity. Freezing allowed that blood to act as a time-traveling resource. Radin explores the unique cultural and technical circumstances that created and gave momentum to the phenomenon of life on ice and shows how these preserved blood samples served as the building blocks for biomedicine at the dawn of the genomic age. In an era of vigorous ethical, legal, and cultural debates about genetic privacy and identity, Life on Ice reveals the larger picture—how we got here and the promises and problems involved with finding new uses for cold human blood samples.

THE GREAT MANCHURIAN PLAGUE OF 1910-1911: THE GEOPOLITICS OF AN EPIDEMIC DISEASE by William Summers

When plague broke out in Manchuria in 1910 as a result of transmission from marmots to humans, it struck a region struggling with the introduction of Western medicine, as well as with the interactions of three different national powers: Chinese, Japanese, and Russian. In this fascinating case history, William Summers relates how this plague killed as many as 60,000 people in less than a year, and uses the analysis to examine the actions and interactions of the multinational doctors, politicians, and ordinary residents who responded to it.

Summers covers the complex political and economic background of early twentieth-century Manchuria and then moves on to the plague itself, addressing the various contested stories of the plague’s origins, development, and ecological ties. Ultimately, Summers shows how, because of Manchuria’s importance to the world powers of its day, the plague brought together resources, knowledge, and people in ways that enacted in miniature the triumphs and challenges of transnational medical projects such as the World Health Organization.

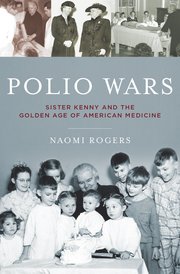

POLIO WARS: SISTER KENNY AND THE GOLDEN AGE OF AMERICAN MEDICINE by Naomi Rogers

During World War II, polio epidemics in the United States were viewed as the country’s “other war at home”: they could be neither predicted nor contained, and paralyzed patients faced disability in a world unfriendly to the disabled. These realities were exacerbated by the medical community’s enforced orthodoxy in treating the disease, treatments that generally consisted of ineffective therapies.

Polio Wars is the story of Sister Elizabeth Kenny – “Sister” being a reference to her status as a senior nurse, not a religious designation – who arrived in the US from Australia in 1940 espousing an unorthodox approach to the treatment of polio. Kenny approached the disease as a non-neurological affliction, championing such novel therapies as hot packs and muscle exercises in place of splinting, surgery, and immobilization. Her care embodied a different style of clinical practice, one of optimistic, patient-centered treatments that gave hope to desperate patients and families.

The Kenny method, initially dismissed by the US medical establishment, gained overwhelming support over the ensuing decade, including the endorsement of the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis (today’s March of Dimes), America’s largest disease philanthropy. By 1952, a Gallup Poll identified Sister Kenny as most admired woman in America, and she went on to serve as an expert witness at Congressional hearings on scientific research, a foundation director, and the subject of a Hollywood film. Kenny breached professional and social mores, crafting a public persona that blended Florence Nightingale and Marie Curie.

By the 1980s, following the discovery of the Salk and Sabin vaccines and the March of Dimes’ withdrawal from polio research, most Americans had forgotten polio, its therapies, and Sister Kenny. In examining this historical arc and the public’s process of forgetting, Naomi Rogers presents Kenny as someone worth remembering. Polio Wars recalls both the passion and the practices of clinical care and explores them in their own terms.

Websites and Webinars

"Epidemic Histories," a website by Paola Bertucci and grad students in HSHM 749

"The Never Ending Story of the 1918 Pandemic" a webinar featuring Joanna Radin, Naomi Rogers, and John Warner

A look back at the devastating pandemic that many see as the closest modern parallel to the COVID-19 emergency, featuring a lecture by Joanna Radin, PhD, associate professor in the section of History of Medicine at Yale.

Other participants:

Naomi Rogers, PhD, professor in the section of the History of Medicine at Yale School of Medicine and the Program in the History of Science and Medicine at Yale University

John Harley Warner, PhD, chair and Avalon Professor of History of Medicine at Yale School of Medicine, and professor of history, American Studies, and history of science at Yale University

Mark R. Mercurio, MD, MA, professor of pediatrics (neonatology); chief, neonatal-perinatal medicine; director, Program for Biomedical Ethics, Yale School of Medicine; director, Yale Pediatrics Ethics Program