COVID-19 Portfolio: In the Media

Carolyn Roberts on Race, Health, and Medicine in times of COVID 19

GLC Director David W. Blight talks with Assistant Professor Carolyn Roberts on Race, Health, and Medicine during the COVID 19 global pandemic.

"Historians: “Distancing” Worked In 1918, Works Now," featuring Naomi Rogers and Jason Schwartz

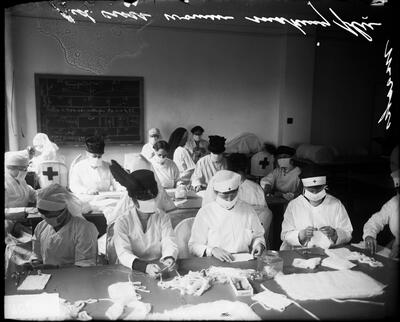

Movie theaters were closed. Public schools shuttered. Parades and other large social gatherings cancelled. Pandemic-wary civilians cautioned to keep away from others to best stem the spread of a deadly flu.

Those “non-pharmaceutical” public health interventions so familiar today in the midst of the COVID-19 outbreak were also widely adopted a century ago as the country, and the world, struggled to contain the Spanish Influenza.

According to two Yale public health historians, those “social distancing” techniques were—and still are—some of the best ways to protect the general public during a pandemic.

Naomi Rogers and Jason Schwartz offered that historical perspective Tuesday during the latest episode of WNHH’s “Dateline New Haven” radio program.

"How Pandemics End," featuring Naomi Rogers

When will the Covid-19 pandemic end? And how?

According to historians, pandemics typically have two types of endings: the medical, which occurs when the incidence and death rates plummet, and the social, when the epidemic of fear about the disease wanes.

“When people ask, ‘When will this end?,’ they are asking about the social ending,” said Dr. Jeremy Greene, a historian of medicine at Johns Hopkins.

In other words, an end can occur not because a disease has been vanquished but because people grow tired of panic mode and learn to live with a disease. Allan Brandt, a Harvard historian, said something similar was happening with Covid-19: “As we have seen in the debate about opening the economy, many questions about the so-called end are determined not by medical and public health data but by sociopolitical processes.”

Endings “are very, very messy,” said Dora Vargha, a historian at the University of Exeter. “Looking back, we have a weak narrative. For whom does the epidemic end, and who gets to say?”

"In Search of Fake and Ancient Panaceas," featuring Barbara DiGennaro

(In Italian)

«La più potente e invincibile (…) arma che usar possino li medici contra ogni veleno totale (…) insanabile, horrendo, pestifero». Ecco che cosa avrebbe suggerito contro il coronavirus lo scienziato bolognese Ulisse Aldrovandi verso la fine del Cinquecento: la Theriaca. Scrisse infatti in un manoscritto, conservato a Bologna e da anni al centro degli studi di Barbara Di Gennaro Splendore, dell’Università di Yale, che grazie all’impiego della carne di vipera nel miracoloso medicamento «siccome la calamita tira il ferro… così la vipera in questa tanto desiderata Theriaca tira a se con gran vehemenza et prestezza ogni et qualunque veleno radicato in qual minera si voglia del corpo…».

"Medical Historian Says Pandemics Are 'Looking Glasses' For Societies," interview with Frank Snowden

In his book, Epidemics and Society: From the Black Death to the Present, Yale medical historian Frank Snowden explores how, for centuries, disease outbreaks have transformed societies across the globe.

Medical Historian Says Pandemics Are ‘Looking Glasses’ For Societies

"Pandemic Narratives and the Historian," featuring Deborah Coen

IN APRIL 2020, we interviewed an international group of leading historians of public health, epidemics, and disaster science. Alex Langstaff (A. L.) asked them to reflect on how history is being used in coverage of COVID-19, and how they themselves are responding to the virus in their research, reading, and work life. Who gets to tell the story of epidemics? And more particularly, who gets to decide when an epidemic like COVID-19 ends? Is 1918 really the best parallel? In general, what are the historian’s tools for understanding pandemics?

"Quarantine, A Historical Perspective," by Barbara DiGennaro

(In Italian)

Risvegliandosi oggi, un medico del Cinquecento non avrebbe alcuna difficoltà a riconoscere la quarantena e i cordoni sanitari che si stanno attuando per il Covid19. Tecnicamente la quarantena è l’isolamento dei malati o dei sospetti malati, mentre il cordone sanitario prevede restrizioni alla mobilità all’interno di un’area geografica definita. Queste sono fra le pratiche mediche che meno sono cambiate nel tempo. Gli abitanti di Firenze nel Seicento, Marsiglia nel Settecento, Hong Kong nell’Ottocento, New York o la Chinatown di San Francisco del Novecento riconoscerebbero senza difficoltà il sequestro delle navi, l’isolamento in casa, gli spostamenti ridotti all’essenziale. Eppure, nonostante le somiglianze, il significato storico della quarantena e dei cordoni sanitari è mutato nel tempo.

Historical Perspectives on STEM - Mary Augusta Brazelton on COVID-19

Mary Brazelton is University Lecturer in Global Studies of Science, Technology and Medicine in the Department of History and Philosophy of Science. Her first book, Mass Vaccination: Citizens’ Bodies and State Power in Modern China, examines the history of mass immunization in twentieth-century China. It suggests that the origins of the vaccination policies that eradicated smallpox and controlled other infectious diseases in the 1950s, providing an important basis for the emergence of Chinese health policy as a model for global health, can be traced to research and development in southwest China during the Second Sino-Japanese War. Her research interests lie broadly in historical intersections of science, technology, and medicine in China and around the world.

Mary discusses the COVID-19 crisis along with the history of public health and modernization in China. Recorded June 10, 2020.

Carolyn Roberts and Sascha James-Conterelli on Race, Health, and Medicine in times of COVID 19

GLC Director, David W. Blight talks with Carolyn Roberts and Sascha James-Conterelli on Race, Health, and Medicine during the COVID 19 global pandemic.

"The Dangerous Race for the Covid Vaccine," featuring Naomi Rogers

Michael Piontek believes his native Germany is putting too much money on one vaccine.

The reason is Donald Trump.

In June, Germany paid a whopping sum for a large stake in German drugmaker CureVac, which was developing a Covid-19 vaccine. Piontek was shocked. “Why CureVac?” he thought. The company’s vaccine is based on promising but untried and untested technology and its manufacturing capacities are limited.

But, months earlier, the American president had insulted German pride by musing about paying CureVac to relocate to the United States. The offer, first reported in the German press under the headline “Trump vs. Berlin,” set off outrage in the Bundestag, elicited cries of “Germany is not for sale!” and led the government to shell out 300 million euros for 23 percent of the firm—an unprecedented move.

"When People Are Data: How Medical History Matters for Our Digital Age," a lecture by Joanna Radin

"What polio in post-WWII America can teach us about living in a pandemic," featuring Naomi Rogers

“Dear Miss Zurovsky,” the editor of The Patchogue Advance, a small Long Island newspaper, began. “Thank you for your letter of September 16th making application for a position as a reporter on this newspaper. I regret to advise you that this job decidedly calls for a man.”

The year was 1946, and my grandmother had graduated from journalism school at the University of Minnesota a few months earlier. But finding a job as a woman presented unexpected obstacles—obstacles that made her angry enough that she kept those letters and, many decades later, passed them on to me.

When I declared my intention to become a journalist in my late teens, she talked to me about her frustrations and read me her rejection letters. And when I entered the workforce, she told me how glad she was that I could finish what she started. In my first months of work at NOVA, I’ve thought of her often. She died two years ago but would have been thrilled (and, I hope, proud) to hear of my joining the staff of a show she loved to watch.

And there’s one more reason my memory has sought those letters during this time. We spoke often before she died about the sexism she experienced as a young professional woman. Only once, though, did she mention another aspect that made her first foray into journalism difficult: the “polio summer.” Everything was closed, she said; everyone stayed home. What was there to write about in a newspaper except polio?

As we drift into the depths of our “coronavirus summer,” I wonder what she would have made of all this. What would have been familiar about the surreal limitations of life in the COVID-19 era? What lessons did polio teach us that over the years we’ve forgotten?

What polio in post-WWII America can teach us about living in a pandemic

"These Uncertain Times" by Beans Velocci

In these times, uncertainty is being actively made.

For the last few months, I have gotten many emails that seem to both lament and deploy uncertainty. I hope this message finds you well in these uncertain times, the emails sometimes say, offering uncertainty as a kind of community. In these uncertain times, we’d like to provide a virtual space for our community to come together.

Under the guise a community, though, comes a kind of justification for cruelty: We understand that you want to plan for the future, but we simply don’t know if we’ll have a teaching position for you in the fall—the coming months are too uncertain. Given the uncertainty of the current moment, we’re going to be laying off 80% of our staff. Good luck out there!

The exaggerated uncertainty of the chirpy corporate email has primed me to notice other forms of strategic uncertainty elsewhere, in the news and in social media.

"Anti-vaccine film targeted to Black Americans spreads false information," featuring Naomi Rogers

When a filmmaker asked medical historian Naomi Rogers to appear in a new documentary, the Yale professor didn’t blink. She had done these “talking head” interviews many times before.

She assumed her comments would end up in a straightforward documentary that addressed some of the most pressing concerns of the pandemic, such as the legacy of racism in medicine and how that plays into current mistrust in some communities of color. The subject of vaccines was also mentioned, but the focus wasn’t clear to Rogers.

The director wanted something more polished than a Zoom call, so a well-outfitted camera crew arrived at Rogers’ home in Connecticut in the fall. They showed up wearing masks and gloves. Before the interview, they cleaned the room thoroughly. Then they spent about an hour interviewing Rogers. She discussed her research and in particular controversial figures like Dr. James Marion Sims, who was influential in the field of gynecology, but performed experimental surgery on enslaved Black women during the 1800s, without anesthesia.

“We were talking about issues of racism and experimentation, and they seemed to be handled appropriately,” Rogers recalls. At the time, there were few indications that anything was out of the ordinary. Except one. During a short break, she asked who else was being interviewed for the film. The producer’s response struck Rogers as curiously vague.

“They said ‘Well, there’s ‘a guy’ in New York, and we talked to ‘somebody in New Jersey, and California,’ ” Rogers told NPR. “I thought it’s so odd that they wouldn’t tell me who these people were.”

It wasn’t until March of this year that Rogers would stumble upon the answer.

Anti-vaccine film targeted to Black Americans spreads false information

"COVID has killed more than one million people. How many more will die?" featuring Naomi Rogers

Nine months into the coronavirus pandemic, the official global death toll has now exceeded one million people. But researchers warn that this figure probably vastly underestimates the actual number of people who have died from COVID-19. And, in a worst-case scenario, one group of modellers suggests that the number of deaths could exceed 3 million people by January.

The one-million milestone was hit on 28 September, according to the COVID case tracker maintained by Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland.

In reality, it is likely that this number “was exceeded some time ago”, says Andrea Gómez Ayora, an epidemiologist at the University of Chile in Santiago. Many deaths related to the coronavirus have gone unreported, she says, particularly in countries where testing isn’t widespread. The death toll will continue to rise as diagnostic capacity increases around the globe.

Nevertheless, this is a significant moment, says Naomi Rogers, a historian of medicine at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. “It’s an even more powerful example of the devastation of this particular pandemic, which, as we live through it, has been very easy to normalize.”

COVID has killed more than one million people. How many more will die?

"A Once-in-a-Century Crisis Can Help Educate Doctors," featuring Joanna Radin

Over the past year, ordinary medical research nearly ground to a halt as researchers focused on coronavirus vaccine trials and treatments. Single-mindedness paid off. Drugmakers developed lifesaving vaccines in record time, and now a third of Americans are at least partially vaccinated.

But ultimately, the pandemic is a once-in-a-century crisis that may force health professionals and medical schools to look beyond the traditional tools of modern medicine and think more broadly about how we train doctors to grapple with public health catastrophes.

"Racial Health Disparities Didn’t Start With Covid: The Overlooked History of Polio," featuring Naomi Rogers

Released: March 16, 2021

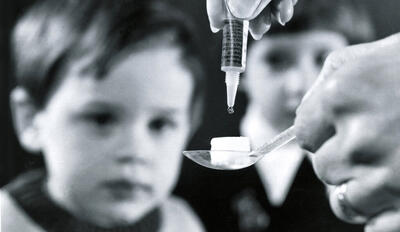

Vaccines began to bring an end to polio in 1955, but – as with the Covid vaccine today – Black communities were slower to receive them.

The coronavirus pandemic has been twice as deadly for Black Americans than whites, and now Black and Hispanic Americans are lagging behind whites in receiving the Covid-19 vaccine.

But the little-known history of polio shows that racial and health disparities are not new. “One of the things that the history of polio tells us is that our racial disparities, health disparities were not invented in the past 10 years, and that very often, they have been deliberately ignored,” Naomi Rogers, a medical historian at Yale, told Retro Report.

Racial Health Disparities Didn’t Start With Covid: The Overlooked History of Polio

"The secret weapon for distributing a potential covid-19 vaccine," an op-ed by Joanna Radin

On Monday, the pharmaceutical company Pfizer announced early data that showed a vaccine it has been developing in partnership with the German drug manufacturer BioNTech was more than 90 percent effective in preventing covid-19. This level of efficacy amazed researchers, including those at my own institution, Yale School of Medicine, who agreed that if the data holds (it has not yet been peer reviewed), then this vaccine would be poised to dramatically curtail the impact of the virus.

This news made headlines, along with Joe Biden’s and Kamala D. Harris’s rollout of a covid-19 task force composed of biomedical experts, suggesting even as the number of daily new infections reached an all-time high in the U.S., a cure was in sight. But, storing and distributing a vaccine — especially the potential Pfizer vaccine, which must be frozen until use at -70°C, around the temperature of dry ice — poses a significant challenge.

The secret weapon for distributing a potential covid-19 vaccine

"SHEA At Yale hosts discussion on vaccine hesitancy and COVID-19 disparities," featuring Joanna Radin

On Tuesday, STEM and Health Equity Advocates at Yale hosted doctors Julian Watkins and Calvin Sun to speak about why certain populations are more critical of the vaccine in context of COVID-19 disparities.

Watkins and Sun, physicians who practice and teach in New York, shared their insights on questions of race and racism surrounding vaccine access. They covered important topics about why many minority populations, especially Black and brown communities, are hesitant toward receiving the vaccine.

“Something that has stuck with me that Dr. Watkins said is shifting the language, talking about how it’s a need to take people’s concerns seriously,” Joanna Radin, associate professor of history of science and medicine, said. “Not just say people are hesitant or skeptical [of the vaccines] or that the problem is with them. This is wrong. Physicians need more willingness to listen.”

SHEA At Yale host discussion on vaccine hesitancy and COVID-19 disparities

"Society and disease: Lessons on pandemic from the pages of history," featuring Naomi Rogers

While doing research as an undergraduate in Australia during the late-1970s, Naomi Rogers stumbled upon some dusty volumes of the British Medical Journal in her university’s medical library. They hadn’t been used in a very long time, but for Rogers — who was searching for debates, from the 1870s and 1880s, about whether women should be admitted to medical schools — there was something “magical” in those pages. At the time torn between a career in music or history, she began to lean toward life as a historian.

Since joining the Yale faculty full time in 2001, Rogers has taught the history of medicine, specializing in disease and public health, gender and health, disability, feminist activism, and alternative medicine. Named a full professor in 2015, she has written about epidemic polio in two of her books, “Dirt and Disease: Polio Before FDR” and “Polio Wars: Sister Kenny and the Golden Age of American Medicine,” and is now working on a book that examines health activism since 1945.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Rogers, professor in the history of medicine and history in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, has been called upon by the media and others to offer a historical perspective on epidemics, public health, science, and medicine. She recently spoke with YaleNews about what past epidemics can teach us about the present crisis, what the pandemic has taught her as a historian, and how a rise in misinformation and anti-science sentiments during a public health emergency is nothing new.

Society and disease: Lessons on pandemic from the pages of history

"The Last Archive" Podcast, featuring Joanna Radin

A fake moon landing. Astronauts carrying space pathogens back to earth. Michael Crichton’s Andromeda Strain. HIV manufactured in a government laboratory. COVID-19 vaccines killing millions. In this episode, Jill Lepore follows a trail of disease stories and conspiracies from Apollo 11 to COVID-19. In part two of our series about the moon landing: Apollo’s splashdown, and the tidal wave of doubt it set off.

"Past Pandemics Remind Us Covid Will Be an Era, Not a Crisis That Fades," featuring Frank Snowden

The skeletons move across a barren landscape toward the few helpless and terrified people still living. The scene, imagined in a mid-16th-century painting, “The Triumph of Death” by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, illuminated the psychic impact of the bubonic plague.

It was a terror that lingered even as the disease receded, historians say.

Covid-19’s waves of destruction have inflicted their own kind of despair on humanity in the 21st century, leaving many to wonder when the pandemic will end.

“We tend to think of pandemics and epidemics as episodic,” said Allan Brandt, a historian of science and medicine at Harvard University. “But we are living in the Covid-19 era, not the Covid-19 crisis. There will be a lot of changes that are substantial and persistent. We won’t look back and say, ‘That was a terrible time, but it’s over.’ We will be dealing with many of the ramifications of Covid-19 for decades, for decades.”

Especially in the months before the Delta variant became dominant, the pandemic seemed like it should be nearly over.

“When the vaccines first came out, and we started getting shots in our own arms, so many of us felt physically and emotionally transformed,” said Dr. Jeremy Greene, a historian of medicine at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. “We had a willful desire to translate that as, ‘The pandemic has ended for me.’”

He added, “It was a willful delusion.”

And that is a lesson from history that is often forgotten, Frank Snowden, a historian of medicine at Yale University, said: how difficult it is to declare that a pandemic has ended.

Past Pandemics Remind Us Covid Will Be an Era, Not a Crisis That Fades